Bro Maintenance

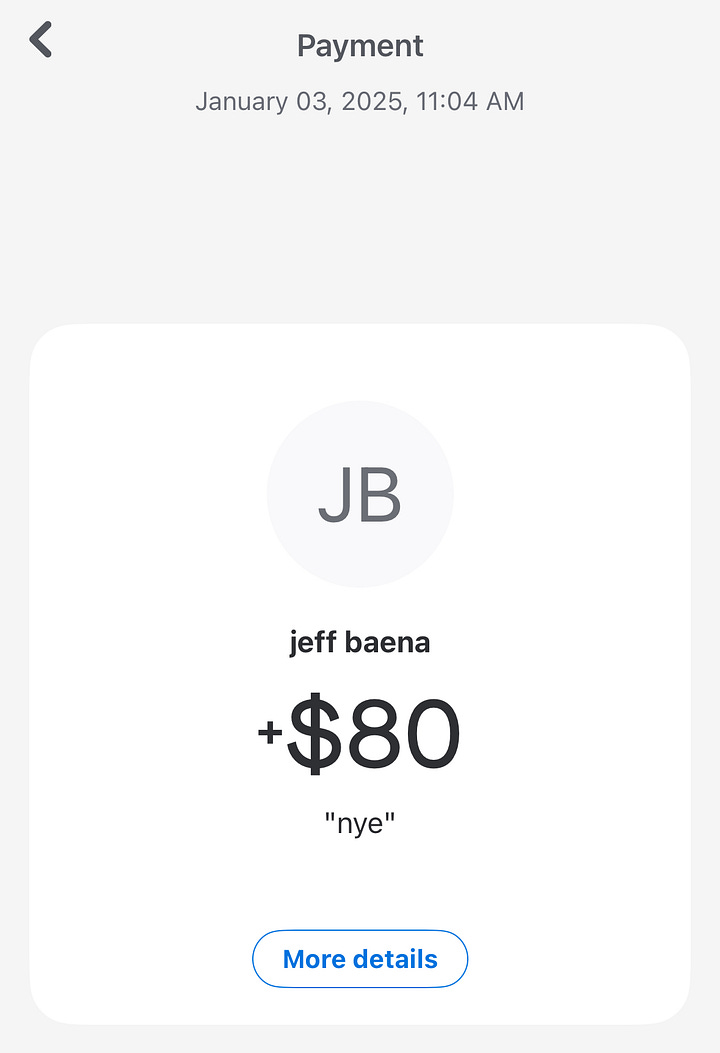

Exactly a year ago today, at 8:04 a.m. PST, I was woken from a dream—a dream about elective suicide and a grey wolf walking away from me—by the sound of CHA-CHING from my phone. Jeff Baena Venmo’d me $80 with the memo “nye.” I lay in bed for about twenty minutes, but my spidey senses kicked in. Jeff was never up that early.

I texted him at 8:27 a.m.: “Saw you were up early. You ok?”

He didn’t respond.

I was distracted by organizing my impromptu trip to India, but I called Jeff throughout the day—straight to voicemail.

That night, I was told Jeff had taken his own life.

The news punched a hole in my chest that still gapes.

Jeff’s body was found at 10:30 a.m., but I believe he intended to be found at 9:00. I have yet to speak with a person who received a message from him after 8:04 a.m. I will never know if he got my text. This sequence plays over and over and over in my head, endlessly.

The memo “nye” was in reference to what turned out to be the last time we hung out, when I paid for everybody and requested $80 Venmos. Jeff tried to pay for himself, but I insisted. I regret that my last words to him were through text: “$80pp for New Year’s. Venmo @BenSinclair.”

Besides trying to solve this unsolvable puzzle, what gets me most is that Jeff only Venmo’d me $80. He could have given me much more. He clearly wasn’t going to use the cash. And he knew that there is nothing I love more than money. He could have at least rounded up to $100.

While this joke is entirely in bad taste—and I am, of course, deflecting this pain with humor—I do believe Jeff would have laughed. We did a lot of that together. While we smoked copious amounts of weed, we made each other laugh, compared our Jewish upbringings, gossiped about our entertainment-industry colleagues, pitched each other projects we were working on, and conjectured life’s ultimate meaning.

Despite Jeff and me being the Odd Couple in our dispositions—I am Oscar and Jeff is Felix—we shared a lot of similarities. We were both writer-directors who smoked tons of weed. We both possessed the skill to bring people together and marshal their talents toward a common goal. We both considered ourselves on the nurturing, feminine side of the Jewish male spectrum, despite being outrageously competitive and headstrong to a fault. We both grew up Jewish in sunny places and attended Alexander Muss High School in Israel, where we both rejected the Zionist indoctrination before it was cool. We were both praised for our intelligence and sense of humor, but we bucked against authority and preferred to make independent work on our own terms. We both loved to jam on synthesizers. We were both closer with our friends than with our own brothers. We both married women with whom we worked and ultimately divorced. We both had a hard time getting over those divorces—because we both have difficulty letting go of control.

But what I am only now realizing is that perhaps our greatest similarity is that we were both very, very sensitive men. And we smoked weed to dampen the suffering caused by our relentless inner self-criticism.

How many jokes did we make to deflect this suffering? How many opportunities to connect were missed in service of the laugh?

Jeff’s friends know how giving he was with his affection. He was full of advice, care, and support. He always wanted you to make your thing. His belief in you was often more certain than yours, and you would go to him when you doubted yourself. He was a committed friend, through and through.

But it was also true that Jeff was very guarded. While he would give hints of his sensitivities, he kept himself out of situations that were outside his comfort zone.

In the last months of his life, I experienced a bit of Jeff’s guard coming down. There are now headlines online revealing the dissolution of Jeff’s marriage, but in his final months he was very secretive about it all. Still, I noticed that he was alone a lot, losing weight, and that his hair had gone completely grey. I confronted Jeff about it, and he let me know that something was up. Perhaps because I had such a public divorce, Jeff thought I could offer guidance on navigating the situation. I do this for a lot of my male friends who are getting divorced.

In early November, Jeff stopped smoking weed because it stopped working for him—it made him even more anxious. Coincidentally, I went off weed too for the month. Jeff was glad to have a friend in not smoking. One night, while I was leaving his house, we stood in the foyer (where he eventually died), and I said, “I know this has been so hard for you, and I see you suffering and wish I could take that pain away. But it has also been an honor to see this tender side of you that not many get to see, and I love you so much.” We hugged for longer than usual.

By Thanksgiving, I was smoking again. Jeff was supposed to come over for dinner, but his anxiety was through the roof, so he stayed home alone. Over the next month, we watched movies together three or four nights a week. Sometimes Jeff and I would take one hit together. But my usage increased back to my heavy normal, and I left him behind in that way. Our one-on-one time diminished, and Jeff spent more time with his female friends.

We spent the final weeks of the year going through our DGA screeners in small groups of friends. One night before a movie, I was smoking alone at his house, and he said to me, “You know, when you’re smoking weed, you’re not as good at talking about feelings and shit.” I conceded that I am a person who has a problem with weed, and that I am probably better off without it.

But despite Jeff telling me weed got in the way of my being there for him, in the year after his death I kept smoking—more than ever, actually, with higher-potency weed, and almost always alone. I didn’t expect that response to his death. I talk with everyone about this gaping hole left in Jeff’s wake—probably too much, with too many people who can’t hold that kind of space.

And honestly, I probably still haven’t found that space for myself to fully grieve. I’m still cracking wise and still chasing chaotic, numinous, ecstatic experiences, hoping for a catharsis that is likely found in stillness. In some ways, I still haven’t allowed myself to fully grieve my divorce from a decade ago. Jeff could not—the pain was too great. But here I am, facing the loss of this person, and perhaps in some ways we saw each other more than either of our exes could have.

When I share all of this with people who haven’t experienced this kind of loss, they don’t know what to do. They say “I’m sorry” and change the subject. People who have been here always do the same thing: they reach out and touch my arm. They listen.

Maybe that’s the point of suffering—to create that connection. Everyone suffers. Those who refuse to feel it may be avoiding that touch.

I’m still figuring out what replaces weed, but for now I’m committed to therapy and mood medications. And when I sense my friends starting to struggle with despair, I confront them head-on. Unfortunately, this year has required a few confrontations. The cost of not confronting it is too high to stay out of it. This is how I can help. Sometimes this help feels like the sunnier side of control.

But in this moment, one year later, I am facing the loss of Jeff. I attempt giving up the control of those feelings without getting stoned. Without deflecting with humor or intellect. I just sit there as it moves through me.

It’s a helpless sort of pain. It just hurts. And it likely always will.

It’s no joke.

cha ching

Still the best thing ever said to me during a loss was, "tell me about them." it's incredible how much more it helped me than a "sorry."

Thanks for letting us get a peek into your friendship.

Sorry to hear of your loss, Ben. As a neurodivergent person working through a backlog of pent up trauma, my relationship to weed mirrors your own. I found a lot to relate to emotionally in the piece as well, with exception to the avoidance of grief. I finally figured out how to pop the cork on that Merlot of Misery, and though it has been difficult at times, I am really thankful I did. Feels like popping an impossibly huge zit. Emotionally. I hope you get to pop yours soon, brodie.